The pulse of history

Rome in May, Silvio Berlusconi and the Gaza-Israel Cease Fire

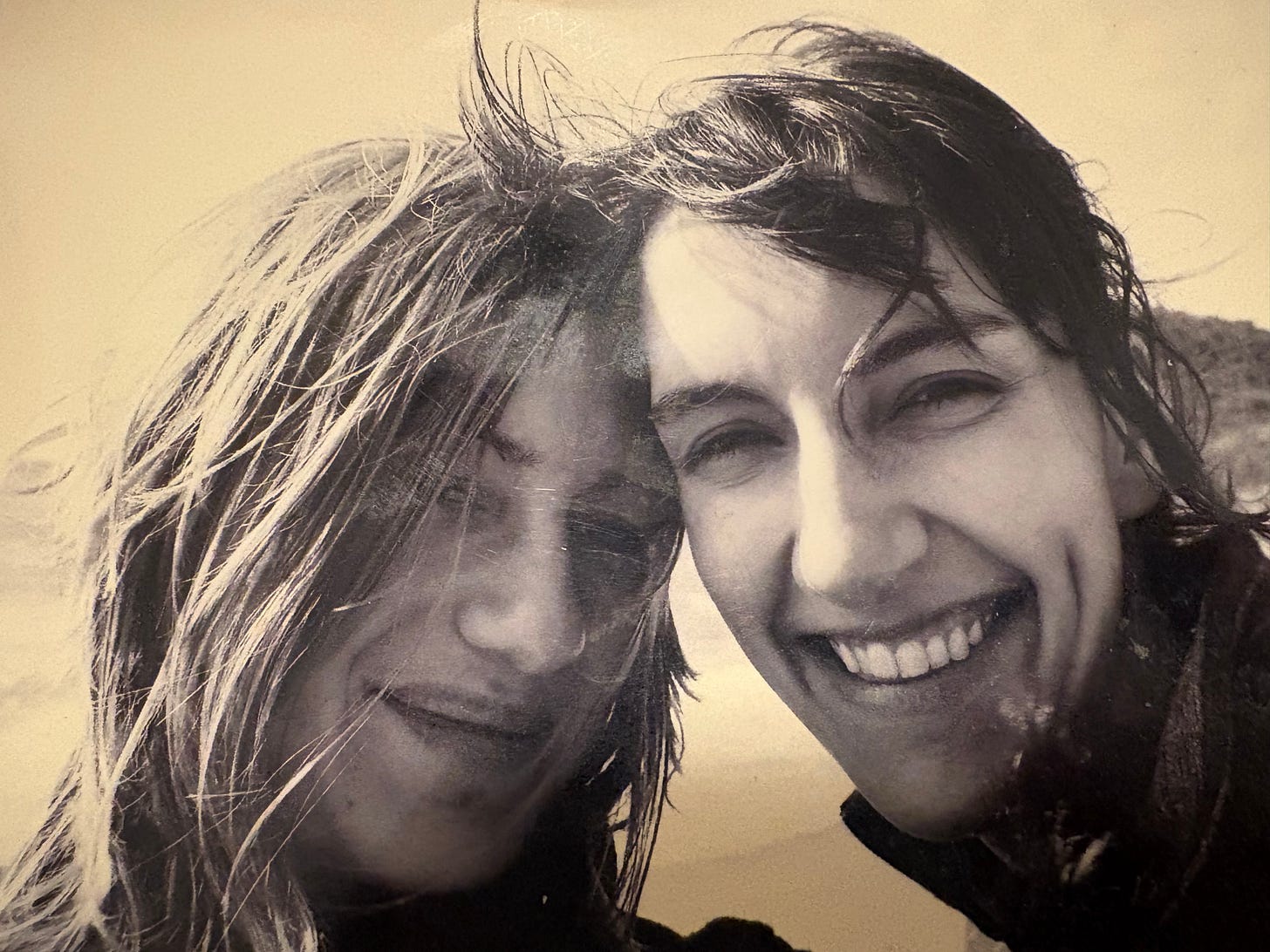

We met in Rome in May. She was standing, frustrated, at the entrance of the Library of the Italian Senate, a beautiful palazzo that most people overlook. It’s just a short walk from the Pantheon, tucked away in a quiet corner of the bustling city. I don’t remember why, but the library technician—a gray-haired man in a neat red uniform customary for all Senate employees, even those tidying the bathrooms—wouldn’t let her in. As a regular, I was there researching Italy’s regional governments in the cool, quiet stacks after fast-paced, increasingly hot days of reporting with a foreign correspondent for German newspapers, much like she had done the year before me.

Somehow, I managed to get her a library card—probably by raising my voice, as I often do when navigating Italian bureaucracy—and she invited me for coffee. Every evening after work, often late at night, we walked across Piazza Navona in the heart of Rome, weaving through vendors luring tourists along the cobblestoned roads, trying to avoid the serious-looking bodyguards of Italian politicians hiding behind their sunglasses in the shadows. Once, they stopped us from bumping into Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s famously self-tanned, ever smirking, longest-serving prime minister. This was despite his seven-year prison sentence and lifetime ban from public office for child prostitution and abuse of power, later spectacularly revoked. We loved writing at the pulse of history.

For 18 years, we never stopped talking, even when she committed to journalism and I to the quiet stacks of the library, the wild mountains, and a life across the Atlantic. She had an incredible energy that matched and accelerated mine. Whether in Rome, Bonn, Berlin, Tübingen, at my wedding on Lake Constance, in Tuscany, or Seattle, we always had ideas and turned curiosity into stories. As my alter ego, she graduated from the Axel Springer Academy, one of Germany’s leading journalism schools, and quickly became one of the most prominent investigative journalists of her generation. In 2020, she began reporting from Tel Aviv, and it became her life.

When the war started on October 7, 2023, I knew she would die. I had studied the Middle East extensively for my Ph.D., and anyone who followed the Israeli-Palestinian conflict knew the powder keg would eventually explode. She had always wanted to be a war journalist. I feared she would be buried under rubble, shot in Gaza, or kidnapped—like so many of her friends that day. I imagined plans to find and save her.

She was among the first foreign journalists to visit the Israeli villages along the border after the attack, reporting on the brutal, systematic rape of women that day and the increasingly catastrophic situation of civilians in Gaza, though she was blocked from entering. She told stories from the abyss of humanity and couldn’t look away. She didn’t live long enough to see the most recent cease-fire deal, which, once again, depends on the political will and mercy of the Israeli government and Hamas. I will never know what she would have written that day, but I know she would have been among the first foreign journalists to visit Gaza and the first to speak to one of the three freed hostages because that was why she did her job: to tell the stories straight from the source, no matter how painful it was.

When Silvio Berlusconi died in June 2023, Tine was the first to text me. We remembered our beginnings, how incredulous we were every time he revived his political career. As a political figure—brash, loud, unconventional, corrupt, and predatorial—he was ahead of his time. Today, he would fit right in.

Tine was different: bold yet principled, driven not by power but by the pursuit of truth. Her work wasn’t just her job; it was her life, writing her therapy and being a journalist her identity. She poured herself into every story, every interview, and every investigation. Her drive was extraordinary and it left her vulnerable to the immense weight of the world she sought to expose.

In a world increasingly dominated by figures like Berlusconi, Tine’s work reminded me—and the world—of what it means to hold power accountable, to tell stories with integrity, and to never look away. But it also underscored the importance of setting boundaries, of protecting one’s inner self from the unrelenting demands of a world that often takes more than it gives. Perhaps Tine gave too much of herself, a cost that even her remarkable strength, humor, and love for life couldn’t overcome.

She showed us the power of storytelling and the need for compassion, but she also left a quieter lesson: that those who carry the weight of history on their shoulders must find a way to carry themselves, too.

A presto,

Eva